Bitwise Operations and Single data types

Bits Bytes and Bitwise

In this example we will explore the Bitwise means of storing user information in a game of tictac toe, and other easy to visualize scenarios

Single vs structured data types.

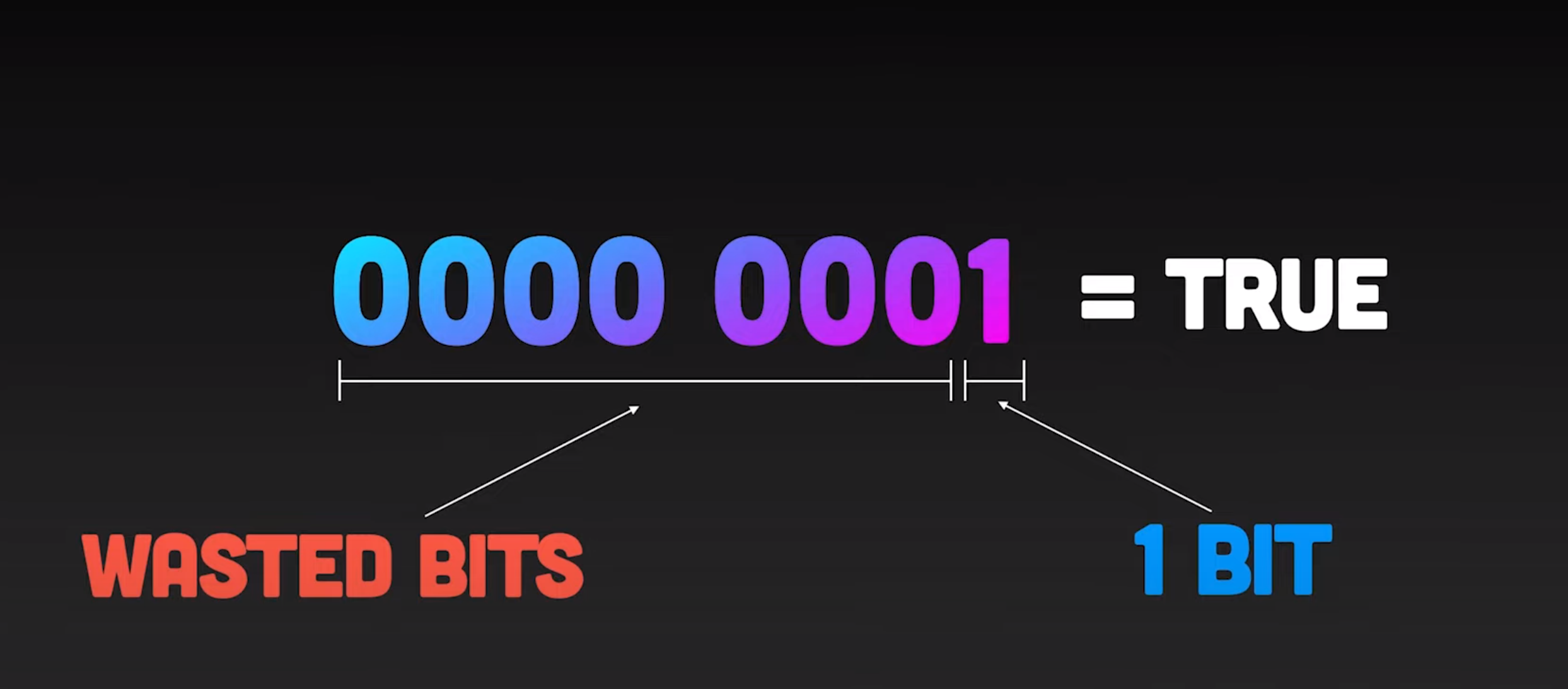

It is actually not very efficient to store true false values in the really large numbers.

Let’s start with an RPG game example where the character has a few attributes that are true or false. You may get away with doing something simple like this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// This is known as structured data type:

struct attributes {

bool hasMagic = true;

bool hasIntelligence = false;

bool hasCharisma = true;

bool canFly = false;

bool isInvinsible = false;

}

However, remember Booleans are stored as a byte in c# and other languages as well, This is because the smallest addressible memory is for a CPU is a byte. This is why storing an array of bools is also just as inefficient as a structured approach. We are wasting bit spaces!

Enter the Bitflags

Lets think in binary bits, assuming you wish to store the following attributes for your character to save the best space for memory:

1

2

3

4

5

bool hasMagic = true;

bool hasIntelligence = false;

bool hasCharisma = true;

bool canFly = false;

bool isInvinsible = false;

We can actually use the individual bits inside an int or in our example a byte to store these attributes , as if we were to represent them as an array the naive way using bool array.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

//essentially your attributes are in an array:

bool[] attributes = new bool[]

{false, false, false, true, false, true, false, false};

//null, null, null, magic, intel, chars, fly, invisi

// simplied we just store the corresponding dec base value in byte:

byte attribute = 20;

// binary 0 0 0 1 0 1 00 = 20

This is called the bitflag. A boolean array efficiently represented! A boolean array is also a boolean set. You can use set theory and boolean algebra to simplify expresssions to reduce complexity for efficiency.

Even tho we know which bit in this byte corresponds to which attribute. As a reference for readability, it is common that we declare an enum to keep track:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

enum attributeFlags {

Invisible = 1,

Fly = 2,

Charisma = 4,

Intelligence = 8,

Magic = 16,

}

Bit shorthand prefix

Instead of calculating what the decimal number for the binary is, we can actually just write the binary representation like this:

Where ‘0b’ prefix indicates that this is a binary literal.

Simple Bitwise Operators:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// AND where (1 & 1 = 1), (1 & 0 = 0), (0 & 0 = 0)

&

// OR where (1 & 1 = 1), (1 & 0 = 1), (0 & 0 = 0)

|

// NOT where ( ~1 = 0), (~0 = 1)

~

// XOR where ( 1 ^ 1 = 0), (1 ^ 0 = 1), (0 ^ 0 = 1)

^

Setting the flags

To begin using this method of storing data. We must first be able to add individual bits to our bitflag. Say we start with the following attribute:

1

2

byte attribute = 4;

// binary = 00 00 01 00

To set the bitflags to store our data we use the bitflag OR-EQUAL operator. Here’s how:

1

byte attribute |= 16;

How it works?

We use BitWise OR-EQUAL,

00000100 |= 00010000 --------------- 00010100We use this to add a bit to our bitflag. This is called “Setting up the bitflag.”

Basically W ∪ X

Remove a bit

To remove a bit we use the AND-EQUAL operator on a compliment of the relavent bit:

1

byte attribute &= ~16;

How it works?

We use BitWise AND-EQUAL, on a ~mask

00010100 &= 11101111 --------------- 00000100We use this to remove a bit from our bitflag. This is called “clearing bits”

new attribute is attributes ∩ X'

Notice how in this example we are not using an XOR operator. The reason for that is that an XOR operator flips the bit using the mask, it doesnt neccesarily turn a bit OFF.

This makes mistaken assumption heavily punished with difficult to find bugs. When working with large numbers of bitwise operations like a calculation jump tables etc. It is best that we stick to reliable, and less error prone operations.

Bitmasking

Contains? Bit masking is a method of filtering whether or not an instance of our bitArray contains the relevant bit. Think of it as:

1

2

3

4

if (user.attributes.Contains("magic"))

{

// DO something

}

But how do we apply this checking for our Bitflags? How do we check if our character which has magic, and other attributes ([0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0]) with the condition of has magic([0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0])?

We would use a bitwise AND operator ( & ):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

byte attribute = 20;

byte filter = 16;

if ((attribute & filter) != 0)

{

// Do something

}

How it works?

We use BitWise And,

00010100 & 00010000 --------------- 00010000any 2 values compared this way, will return a value if there is a match, and returns 0 if there are no matches.

Basically if (W ∩ X is not an empty set)

Fully Contains ? We can also use the same logic to check whether an an attribute contains all the relevant bits.

1

X ∈ W ?

We can compare the result of the end operator to see if it is the same as the filter.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

byte attribute = 20;

byte filter = 16;

if ((attribute & filter) == filter)

{

// Do something

}

How it works?

If X is a subset of W, where all elements of X is inside of W then:

Is Equal Comparisions

We can use 2 masking operation to compare 2 flags to see if they both contain the same particular bit.

1

2

3

4

if ((attribute1 & mask) == (attribute2 & mask))

{

// Do something

}

Non-boolean functions

Since we are using our byte as a kind of boolean array. What if we want to instead do more complex array-like operations like retrive the index of the first true, or any Indexing operations.

Just like set theory, we have to use functions to retrive the relevant sets:

Example problem

Definition: A collection of sets E is said to be indexed by a set A if and only if there is a function F from A onto E . In this case we call A the index set of E , say E is indexed by A, and represent F(a) by Ea . In particular, E is indexed by A means E={Ea}a∈A .\

Suppose that we have sets {a,b,c}, {a,d,x,y}, and {c,u}; we can form the collection E={ {a,b,c},{a,d,x,y},{c,u} } Now let A={1,2,3}; we can define a function f:A→E by f(1) = {a,b,c} f(2) = {a,d,x,y} f(3) = {c,u}

Non-boolean Operator - shifting

One neccesary operation when working with Bitwises, are shifting operations that would allow us to shift the bits in a bitArray. These operations cannot be done using traditional true false “AND” or “OR” and “XOR” operations.

Forward shift We use the forward shift operator to shift all the bits forward by an ammount.

1

2

3

// Given X in binary is 00100

x = x << 1;

// Outputs 01000

Back shift To shift a bit backwards, we use the backshift operations:

1

2

3

// Given X in binary is 00100

x = x >> 1;

// outputs 00010

The syntax for bit shifts are as follows:

1

2

3

4

x >> n

Where n represents the shifting ammount in integers. n = 1 would shift 1 bit,

2 would shift 2 bits...

Index of First and Last bit

In programming languages like C++ and C, they have a function called “BitScanForward()” that returns the index number of the first “ON” bit in a bit-array.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

// _ndex_

// [out] Loaded with the bit position of the first set bit (1) found.

// _Mask_

// [in] The 32-bit or 64-bit value to search.

BitScanForward(&index, mask);

We do not have such functions in C# or any higher level languages, so instead we loop thru the bit-Array using the >> or << bit shift operator as increments and return the first matching bit found:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

// Get Least Significant Bit Position (first bit in 000101 is at 0)

static Int32 GetLSBPosition(UInt64 v) {

UInt64 x = 1;

for (var i = 0; i < 64; i++) {

if ((x & v) == x) {

return i;

}

x = x << 1;

}

return 0;

}

// Get Most Significant Bit Position (last bit position in 000101 is at 3)

static Int32 GetFSBPosition(UInt64 v) {

UInt64 x = 1UL << 63;

for (var i = 63, i >= 0; i--) {

if ((x & V) == x) {

return i;

}

x = x >> 1;

}

return 0;

}

Not Fast Enough?

There are faster techniques for returning bitArray indexes, known as “De Bruijn sequence approach”

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/37083402/fastest-way-to-get-last-significant-bit-position-in-a-ulong-c

Get bit at an Index

To retrive a bitMask from a given index position, we can simply access that particular index using shifting operations and shift our mask to the interested bit:

1

2

3

static byte GetBitMaskAtIndex(byte bitArray, int index){

return bitArray & (1 << index);

}

To retrive a bool from a given bit from a bitArray. We perform a similar operation, but instead we push the particular bit to the first index and “AND” it with 1 to return a boolean value.

1

2

3

static bool GetBitAtIndex(byte bitArray, int index) {

return (bitArray >> index) & 1;

}

Practical Example: Unoptimized Implementations

Let’s go with an easy to understand Tictactoe implementation. I will be showing 2 solutions to a tictactoe game. One is a typical beginner’s implementation so the logics of implementing the game is easily understood and intuitive, the alternative is with using bitwise operations.

There are a few rules in a tictactoe game. If we were to implement them in code, we need to keep track of coditions of the game states namely:

- Who’s turn

- The board

- Winning condition

- Valid moves

The board

Let’s start with the most basic feature. We need a data structure to store the state of the game.

- Is the board empty?

- What squares are being occupied?

Since the game board is a 3 x 3. We could implement a simple 2D array like so: Where string can be empty (“”), “X” or “O”.

1

var string[,] = new string[3,3];

Turn

Then we need to define who’s turn it is. Since there’s only 2 possible turns, we can use a bool, where true is X and false is O.

1

bool turn = true;

Winning condition.

Next we need to check the winning condition of the game. If we make a move, check whether or not our board contains the winner. In a tictactoe game the winning conditions are defined as if any rows or column contains 3 vertical matches, or 3 horizontal matches, or 3 diagonals. A total of 8 conditions

We can code the logics the brute force way where each turn made, we check wether the board has the same elements in a given row or column or diagonal.

Using early return paradigmn. If there are no winners, then if all squares are occupied, it is a draw, else the game goes on.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

private string _winning_line;

// Wining and Losing Checkings

private string _Winner(out string _winning_line)

{

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

if (grid[i, 0] == grid[i, 1] && grid[i, 0] == grid[i, 2]) {

_winning_line = "row" + i.ToString();

return grid[i, 0];

}

if (grid[0, i] == grid[1, i] && grid[0, i] == grid[2, i])

{

_winning_line = "col" + i.ToString();

return grid[0, i];

}

}

if (grid[0, 0] == grid[1, 1] && grid[0,0] == grid[2, 2])

{

_winning_line = "diagonal1";

return grid[0, 0];

}

else if (grid[0, 2] == grid[1, 1] && grid[0, 2] == grid[2, 0])

{

_winning_line = "diagonal2";

return grid[0, 2];

}

else if (!grid.Cast<string>().Any(s => s == null))

return "Draw";

else

{

_winning_line = "";

return "";

}

}

Making moves:

It is very simple to implement a make moves function in this case. We first check if the square is empty. If its empty, make the move, else, dont. And we also check the turns and insert the appropriate string.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public void Move(int row, int col)

{

if (board[row, col] != "") return;

if (_turn)

{

grid[row, col] = "X";

_turn = false;

}

else

{

grid[row, col] = "O";

_turn = true;

}

}

Putting it together:

Putting everything together, we have something like this.

- Player makes a move. If move is valid, the board changes

- Prints the board into the console for visualization.

- Call a the win condition checking, if it returns anything other than empty or draw. We have a winner

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public void MakeMove(int row, int col) {

PrintBoard();

Move(row, col);

if (_Winner() == "") return;

if (_Winner() != "Draw"){

Console.WriteLine("Winner is: " + _Winner + " on " + _winning_line);

}

else

Console.WriteLine("Draw!!");

}

Optimized Bitwise Implementations

Now we figured out the basic mechanics of the tictactoe game, we can make much much better optimizations.

The board

Although the more intuitive approach of using a 2D array is pretty easy. In terms of space efficiency, this is too unoptimized. Imagine if you were to implement the same game on an Arduino or any embeded system, this is an unneccasary waste of space.

If it is simple enough we should always use a 1D array to represent our positions.

1

var byte[] board = new byte[9];

A byte board is simple enough. a byte is smaller than a string, and each index corresponds to each square in our board now flatten. And the entries could be 0 for empty, 1 for X, 2 for O.

1

2

3

0 1 2

3 4 5

6 7 8

But we can do better.

Instead of using 9 bytes of data to represent the board. We could use only 4 bytes. This is where the concept of Bitboard comes in:

1

uint16[] board = new uint16[2];

We use 2 uint16 values, but not as an integer number, instead its internal bits as a way to store spatial information. 1 uint16 for each side.

uint16[] board = {bitArray for X, bitArray for O};

so the board would look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// What humans see:

[X, , ]

[O, O, ]

[ , , ]

// What is being stored:

for X for O

1 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 1 1 0

0 0 0 0 0 0

Since the board only has 9 squares, and a byte is not big enough to store it, we have to use an uint16, as it is the next largest single data type for us to use. The remaining fits can be left unused.

Why uint16?

The U in uint16 stands for unsigned integer, meaning it doesnt have negative numbers. We often use unsigned integers for bitwise operations as the last bit for any integer is usually reserved for negative number representations, we dont want that as it would mess up our expectations of bitwise operations results.

In c#’s dotNET standards. we would useushortinstead, asuint16is depreciated. For the examples here, we useuint16as it is more readable.

Checking for wining conditions

To check for winners we still use the same trick of finding matches by scanning over each rows and columns and diagonals, however, instead of loops and checking each indexes on a row or column for matches. We would use a bitmask. This operation is much much faster.

A bit mask to represent each possible winning condition. A total of 8.

1

2

3

4

5

6

// internally represented as:

1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 and some 5 more.

var winingPositions = new uint16[8];

In this case it is easy enough to count by hand and paper, and hard code the winning conditions’ numeric representation into the array. In larger more complex projects. These are procedurally computed using vector maths and stored in hashsets during the initialization phase.

We can perform this following operation to evaluate wherther theres a winner:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

for (var i = 0; i < 8; i++){

if (board[0] & winingPosition[i] == winingPosition[i])

return "X is winner!";

if (board[1] & winingPosition[i] == winingPosition[i])

return "O is winner!";

}

return "";

For draws? We would check if all squares are occupied using a bitwise “OR”. We know that the 2 position boards never intercepts, so if the union of the 2 boards results in a full board. Then it is a draw.

We know the number that corresponds to 9 bits “ON” state is 511 (Calculated by hand of course)

1

2

if (board[0] | board[1] == 511)

return "Draw!";

Making moves

We can also just as easily mask out the valid moves. In fact, This is the same mechanics as calculating draws. But exposing a move function to the end User, either on a GUI or as a class Method requires some translation, as we shouldnt expect everyone to know bitwise operations, and feeds in a bitmask as input a parameter for a move.

We check if a move is valid by doing the bitmask:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

if ((board[0] | board[i]) & moveMask != 0) {

// This square is not empty! Cannot make move here

}

else {

// Since turn is binary and our board is also 2 entries...

board[turn] &= moveMask;

turn ^= 1;

CheckWinners();

}

Here we can flip the turn very easily with just a bitwise “XOR” operator.

Calculating the moveMask

How do we calculate the moveMask say if we were to expose our function makeMoves function to an end User, where it accepts an index number or a Vector2 as an input.

There are a few solutions to this:

Precalculated jump tables: Write down all possible moveMask by hand, and hard code them into a Dictionary where the values are the moveMask and the keys are in Vector2 or integer index.

Bitshifts by Index ammount You can compute the moveMask by using bitshifts with the ammount of Index.

1.and2.combined

We have to be clear here and set a standard of how we would address an Index or a Vector2 input. Messing up this standard creates lots of bugs, and it gets even messier to diagnose and fix on large projects with hundred of lines of bitwise jump tables.

1

2

3

4

5

// where the bottom right corner represents the first bit

Visual: Index: BitArray:

[X, , ] 8 7 6 1 0 0 0 0 0

[O, O, ] 5 4 3 0 0 0 1 1 0

[ , , ] 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

So, we here’s how we can compute the bitmask:

1

2

3

4

static ushort IndexToBit(int index) {

ushort outputMask = 1;

return outputMask << index;

}

With these references, we can procedurally construct our dictionary during initialization and avoid doing the calculations by hand.

References

Bitwise Operations in Unity: https://www.udemy.com/course/games_mathematics/